Granville Austin, in Indian Constitution: Cornerstone of a Nation,argues that the Indian constitution is a product of the idealism of the Indian Independence movement, which was rooted in “an awareness of the plight of the mass of Indians”, that the constitution was “a declaration of social intent” and an “intricate administrative blueprint” made possible by the “extraordinary sense of unity among the members” who “disagreed hardly at all about the ends they sought and only slightly about the means for achieving them”.

On the question of untouchability, Austin summarily states that the Fundamental Rights Sub-Committee adopted the provisions on untouchability with “swiftness” and that the inclusion of Article 17 (abolishing untouchability), Article 15(2) (prohibiting the imposition of disability in use of public places on account of religion, race, caste, sex, or place of birth), and Article 23 ( prohibiting forced labour) demonstrated that fundamental rights were framed to “foster the social revolution by creating a society egalitarian to the extent that all citizens were to be equally free from coercion or restriction by the state or by society privately”.

Probing into the archives of the Constituent Assembly , one discovers that it is not true that Article 17 was adopted without controversy or discussion.

K.M. Munshis’s draft was tabled in front of the Sub-Committee on Fundamental Rights (SCFR), stating the provision quite simply as “Untouchability is abolished, and the practice thereof is punishable by the law of the Union.”

Harnam Singhs draft tabled on 18th March 1947 adopts a different framing: “The recognition of untouchability shall be a crime in India.” In addition to prohibiting caste based discrimination in hiring for public offices, land ownership, freedom of trade and occupation, and access to public spaces were guaranteed in this draft.The variation in phrasing indicates the presence of divergent views on whether criminalisation was the appropriate legal remedy.

The most serious challenge was presented through the States and Minorities proposal backed by Dr. B.R. Ambedkar and H.J. Khandekar. On March 24, Dr. Ambedkar tabled his “States and Minorities” proposal as a report to the Sub-Committee on Fundamental Rights. States and Minorities read like a mini-constitution; it is explicitly concerned about the civil rights of Dalit citizens. In foregrounding the rights to equality before the law available to all citizens it explicitly nullifies any enactment, custom, or interpretation of the law that discriminates against any citizen. This stems from Ambedkar’s sociological analysis that untouchability thrives in Indian society not due to illegality but due to the legality afforded to discrimination and exploitation through religious law and custom.

The report documents in painstaking detail the forms that untouchability can take, whether that’s denying full enjoyment of public accommodations, educational institutions, public conveyances, tanks, and other public spaces, the practice of forced labour, social boycott, or caste-based discrimination by government officers and private employers. It categorises these practices as cognisable offences and enjoins the union government to enact statutes to this effect. In doing so, it foregrounds the right to equal access to publicly maintained institutions. It forbids caste-based discrimination in public employment and calls for proportional representation of Dalits within the public services.

The report moves beyond the simple criminalization of untouchability and imposition of social disabilities however. It also imposes special responsibilities on the union government to protect Dalit communities from persecution, for investment in secondary and college education for Dalit citizens, and their resettlement by the state so they may escape oppression in villages. It also calls for separate electorates for Dalit citizens and proportional representation in the legislature.

Dr. Ambedkar, in his explanatory notes to his proposal, notes how “rights are real only if they are accompanied by remedies” and how “unequal treatment has been the inescapable fate of the untouchables of India”. He cites reports from the government of Madras written in 1892 that outline various forms of oppression faced by “Pariahs” who rebelled against the caste order, including harassment through malicious prosecutions in courts, destruction of their huts, forcible burning of their crops, obstruction of their access to public spaces, and obstruction of the flow of water into their lands. He notes how the legal system has been weaponised by caste Hindus to persecute Dalits and how Dalits face barriers to accessing the legal system:

“It will be said there are civil and criminal courts for the redress of any of these injuries. There are courts, indeed, but India does not breed village Hampdens. One must have the courage to go to the courts, money to employ legal knowledge, and the means to live during the case and the appeals. Further, most cases depend upon the decision of the first court; and these courts are presided over by officials who are sometimes corrupt and who generally for other reasons, sympathise with the wealthy and landed classes to which they belong. The influence of these classes with the official world can hardly be ignored”

Dr. Ambedkar clearly expresses distrust of legal and administrative institutions and the difficulty of purely legal solutions that remain a mainstay of discourse on Dalit rights even today. His solution at the time was for the constitution to contain protections for civil rights along the lines of the Civil Rights Protection Acts of 1866 and 1875 enacted in the United States of America.

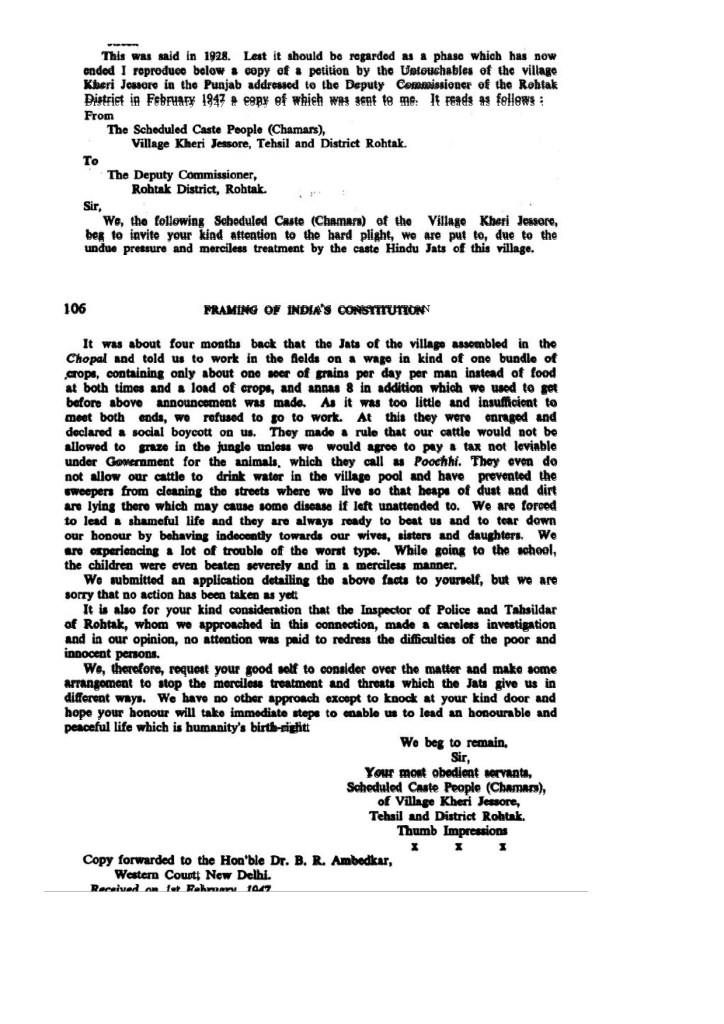

In support of his provisions explicitly categorising boycotts as a cognisable offence, Ambedkar reproduces a letter from “The Scheduled Caste People (Chamars), Village Kheri Jessore, Tehsil and District Rohtak” that was sent to him.

The letter, in great detail, outlines how Dalits who had refused to work for reduced wages (“only one seer of grains per day per man instead of food at both times and a load of crops and annas 8 in addition which we used to get before”) were subject to a social and economic boycott. They were denied the ability to graze their cattle in the jungle or to drink water in the village pool, were denied the ability to work as sweepers in the village,humiliated with casteist slurs, were beaten, and their children who attempted to go to school and their women were subject to indecent behaviour.

Ambedkar uses this letter to argue that the plight of the untouchables, specifically in rural areas, cannot be said to have improved despite reform movements and that criminal sanction for social boycotts and the practice of untouchability was necessary. He does so while also using the petition as a way to underscore how economic dependency of Dalit citizens on Caste Hindus impedes their ability to excercise their rights and seek justice. In this way Ambedkar ties the exercise of Dalit civil rights to demands for criminalisation of untouchability.

He also indicates that criminal laws are necessary but insufficient to eradicate untouchability due to the economic and social dimensions of caste. In discussing the need for resettlement of Dalits, Ambedkar argues that there are social and economic reasons for considering the proposal seriously. He says, “India is admittedly a land of villages, and so long as the village system provides an easy method of marking out and identifying the untouchables, the untouchable has no escape from untouchability”. And that since Dalits are “a body of landless labourers who are entirely dependent upon such employment as the Hindus may choose to give them and on such wages as the Hindus may find it profitable to pay,” he thinks it is “obvious that there is no way of earning a living” which is open to Dalits “as long as they live in a ghetto as a dependent part of the Hindu village”.

In doing so, he argues for “State Socialism” that would plan economic life to be equitable. It is evident that Ambedkar thinks the untouchability problem would be impossible to solve without restructuring rural life.

“States and Minorities” offers up a charter for Dalit civil and political rights as group rights in independent India. These documents are an alternative we ought to consider while evaluating the contingency of choices made within the Constituent Assembly and the Parliament concerning the untouchability problem.

Within the SCRF, there was no response to Dr Ambedkar’s proposal for 5 days when, on March 29th 1947, it was decided that the question should be deliberated at a future date. The draft report of SCFR dated April 3rd, 1947, adopts the formulation: “‘Untouchability’ is abolished and the practice thereof shall be an offence”. With B.N Rau’s report stating that the exact parameters of what is meant by untouchability will “have to be defined in statutes passed by the parliament.” The final report of the SCFR reverts to the “untouchability in any form is abolished” wording on April 14th 1947.

Dr. Ambedkar’s proposals seem to have vanished in the air. Some negotiation or deliberation has occurred that can only be found by conducting deeper archival research that investigates the private papers of individual members of the SCFR. Niraja Gopal Jayal speculates that this retreat from “States and Minorities” might have been part of a bargain by Ambedkar to allow for a weakened Article 17 in exchange for affirmative action in educational institutions and the legislature. But, absent specific evidence for that interpretation, it would not be incorrect to state that this was an instance of an unresolved conflict among lawmakers.

In the next post, we will discuss deliberations on Article 17 in the Sub-Committee on Minorities.

References:

1) B Shiva Rao, The Framing of India’s Constitution: Selected Documents Vol. 2,( NM Tripathy, 1967)

2) B.R. Ambedkar, States and Minorities, (1945)

4)Niraja Gopal Jayal, Citizenship and its Discontents, Ch 5 the “Unsocial Compact” (Harvard University Press 2013) 136-163.

5)Granville Austin, Indian Constitution: Cornerstone of a Nation, (Clarendon Press Oxford, 1966)

Leave a comment